Afropean’s Tommy Evans exchanges notes on poetry with fellow lyricist Saraiya Bah, one of London’s finest emerging spoken word artists. As a poet, writer and performer, Saraiya posits herself as a chronicler of life as a London-based young Muslimah. Here she discusses the pitfalls of being a potential role model, her creative process and what can be considered a “permitted” performance style. Rallying the support of other female poets through “coffee creatives” and disseminating her work through modern forms of technology, Saraiya is clearly a 21st century Afropean griot in the making.

TE: When did you fall in love with poetry?

SB: I’ve always loved stories. The first poem I wrote was at the age of 9 and I recited it in assembly because it was that good! From there I was in the gifted and talented programme between the ages of 10 and 14 writing short stories. I fell in love with the literary greats like HG Wells, Wordsworth and Edgar Allan Poe; as for Rumi, I discovered him later in life and really appreciated his art form. I’d eventually lose confidence in my writing and left it for four years until a hardship occurred: my grandmother became terminally ill. I almost lost myself only to rediscover whom I was through writing again to get to the point where I am now.

TE: Did you find poetry helped articulate those emotions?

SB: Definitely. When I receive feedback on my poetry I find that the emotions audience members feel get connected back to their own experiences. Maybe people are not supposed to understand exactly what I’m feeling because ultimately we are all going through our own individual trials and everyone is tested differently. That’s given me an idea for another poem…

TE: Glad to be of service! So you’re saying the poet or artist is able to articulate emotions, ideas and experiences in a way that your “average” layperson might not? As a consequence, the listener or observer is then drawn to them and sees aspects of their own self in that public figure or role model but maybe it isn’t an accurate assessment – perhaps they’re just projecting their own personality onto them. We don’t see the world for what it is but for who we are.

SB: Definitely. And maybe we’ve inadvertently discussed what a role model is. Oh sugar! I am a role model.

TE: Like it or not!

SB: This is disappointing…

TE: Why? You no longer have free reign to act without account?

SB: Were someone to say I’m a role model it’s like: oh my gosh, so now I have to be even more careful how I conduct myself but perhaps that’s me looking at it in a negative way. I could look at it positively and be like: well, I’m a role model that means I’ve actively got to be a better person on all fronts.

TE: It can be an issue when the art and the artist converge in the mind’s eye of the audience and they don’t separate the two. I think our art needs to come with a public health warning: just because a creative produces beautiful art it doesn’t mean they possess a beautiful soul as well.

SB: Definitely. If you’re a punk rocker who happens to listen to classical music to unwind no one is going to want to know about your need for R&R. They don’t care about that. You have to be that punk rocker 24/7! As a role model there’s an expectation and you have to hit that benchmark every time. If you supersede the benchmark even better but you have to keep on going up and up and up. Going to popular culture now: every album the Rihannas and Beyonces of the world release or every concert they perform must be bigger and better than before. Kanye West worked himself into exhaustion to surpass his previous artistic accomplishments. Now scaling it back down to me, every poem I write has to be better than the one before; there’s a standard I have to hit every single time. It can be a bit difficult because some poems you can just write on the spot and can take five or ten minutes. Alternatively, some poems can take a year or longer to write depending on the content. There are some poems I’ve written where I thought I’d finished them but upon revisiting them I added more to the piece. That’s why I love poetry so much because there is no “The End” to it. Plus poems are super short to write and complete; I do a wide range of writing and although I love writing prose I hate it at the same time because I can never finish! That’s one of my goals for 2017: to complete the supernatural fiction story that I started in 2010.

TE: Sounds scary. Is there a clown in it?

SB: No clowns!

TE: Phew – clowns are terrifying! Back to the creative process. I’m intrigued as to how you go about composing poems. I know how I do it – when inspiration hits I just have to write.

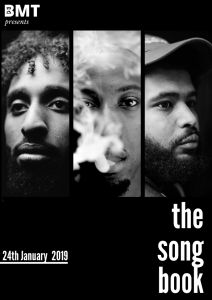

SB: That’s pretty much what I do myself [shows poetry book].

TE: Just looking at the way you compose words on a page I’m struck by how structured it all is. I, however, have never been able to write in a linear order. I flood the page with thoughts and rhyming couplets then connect these disparate themes with scrawled lines. My writing resembles the random ramblings of The Joker from Batman!

SB: This work is not completed. You’ll see a lot of scrubbing out and redrafting of things and whatnot. I never really type things. I always write on paper because I like the visceral feeling of writing – I’m a geek.

TE: Likewise.

SB: One time I nearly lost my book, which had A LOT of my work in it, and I nearly had a heart failure! I didn’t realise until I needed to write in it but I’d left it at an event where I’d recited my poetry. Fortunately, the organisers found it and kept it for me. Basically, I have completed poems and incomplete ones in these folders on my iPhone. If I’ve written something down on paper I take a photo of it.

TE: A fascinating technique. That’s your back up. Your “cloud”.

SB: In case I ever lose a book.

TE: I’m still relatively new to spoken word and very much approach poetry with a rapper’s sensibility. One thing intrigues me: how are poets “allowed” to perform on stage reading from a book? That’s “cheating!”

SB: [Laughs].

TE: Do you not memorise your work beforehand?

SB: No!

TE: I’ve seen so many poets do it.

SB: We can get away with it!

TE: How is it you’re “allowed” to do that?

SB: Personally, it’s a crutch I’ve been holding onto but I’ve been told categorically by a friend of mine – who doubles up as a mentor – that I’ve got to dead reading from a book, iPad or phone to move forward and break that potential disconnect with the audience. However, traditionally speaking, poets would read from the page because they’re churning out so much material they don’t have the time to memorise everything and then recite it.

TE: I don’t think there’s a right way or wrong way there’s just different ways…

SB: Does it annoy you a bit?

TE: Not at all. It just intrigues me! But my background is not in spoken word or poetry so I’ve come to this discipline via a very different route. When I started performing spoken word I still had my rapper’s head on so I’d literally prowl the stage back and forth because standing still felt like “cheating;” it didn’t feel like much of a spectacle for the audience. However, the ambience of going to see Septa live is different to seeing Suli Breaks live; they’re both fantastic at what they do but they’re masters of two very different disciplines. Which is cool. When you’re performing as a rapper or grime artist on stage the principle objective is to literally “move the crowd” (like Rakim said) physically as well as emotionally (and intellectually to varying degrees) whereas a poet’s primary goal is to move audiences intellectually and emotionally.

SB: That being said, having observed other poets who do use apparatus-

TE: That’s an interesting way to describe it.

SB: There’s some who are not engaging and are just getting the words out; there’s not been much thought devoted to the actual performance. Whereas you have some people who use apparatus also have a technique like… Remember when you were in primary school and your teacher would read to you? Some teachers would just read whilst there were some teachers who would hold the book like so and employ big hand gestures and facial expressions whilst knowing how to drop lines. You’ll have poets who know how to emulate that style. I’m still discovering myself as a performer. However, I do feel I’ve mastered the art of evoking an emotional response from the crowd based on the control of my voice and how much passion and intonation I inject into it. Some of my poems I’ve memorised and I’ll feel comfortable reciting without a book but the majority of the time I rely heavily on my “crutches” so now I have to let them go! At the moment I’m going through-